The Five Sisters

Siobhan McLaughlin

A_Place Gallery

Installation view, The Five Sisters, Siobhan McLaughlin, A_Place, 2025

Installation view, The Five Sisters, Siobhan McLaughlin, A_Place, 2025

Installation view, The Five Sisters, Siobhan McLaughlin, A_Place, 2025

Siobhan McLaughlin, No More Tip Men, 2025, 80 x 100 cm, earth pigment from Five Sister shale, earth pigment from Gunwalloe and oil paint on sewn remnant materials

Siobhan McLaughlin, Fragment of the Five Sisters III, 2025, 12 x 15 cm, earth pigment from Five Sister shale, earth pigment from Gunwalloe and oil on remnant linen; Fragment of the Five Sisters I, 2025, 18 x 12 cm, earth pigment from Five Sister shale, earth pigment from Gunwalloe, earth pigment from Geevor Mine, and oil on remnant material; Primary Succession, 2025, 44 x 31 cm, earth pigment from Five Sister shale on sewn remnant materials

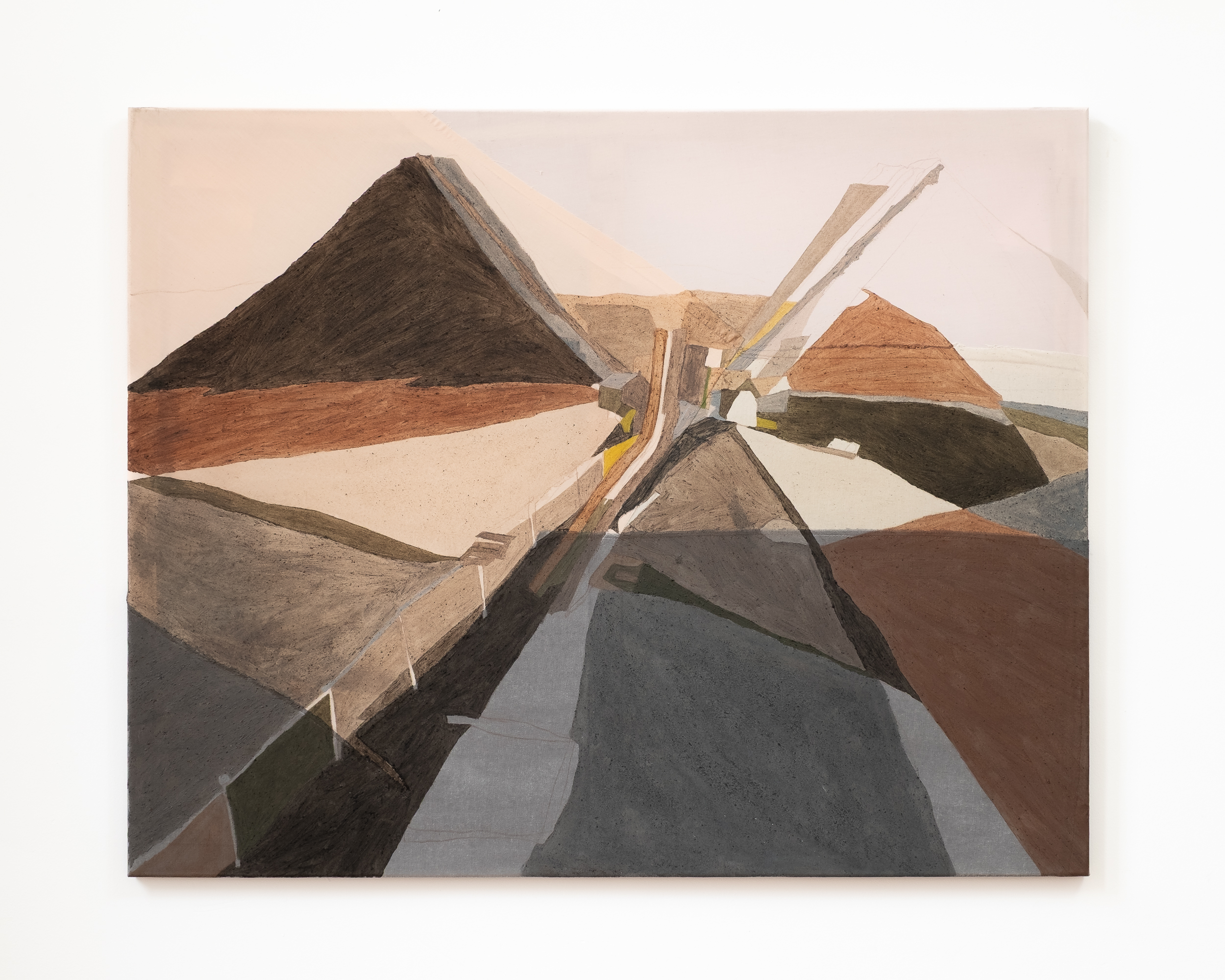

Siobhan McLaughlin, Date of Exhaustion, 2025, 80 x 100 cm, earth pigment from Five Sister shale, earth pigment from Gunwalloe, oil and acrylic on sewn remnant materials

Siobhan McLaughlin, Pioneer Species, 2025, 42 x 31 cm, earth pigment from Five Sister shale and acrylic on sewn remnant materials

The Five Sisters

Siobhan McLaughlin

A_Place Gallery

07/11 – 21/11/2025

At the heart of Siobhan McLaughlin’s work, is a desire to reconnect us with what it means to exist in relationship to the land. For many artists today, and certainly historically, this well-meaning impulse usually results in work that reflexively depicts a romanticised version of the ‘view’. A visual cue implying that there exists a version of the land that is pure nature. But what even is the natural state? The British Isles have a history of human intervention that is so old that many of its views and features deemed to be ‘natural’ are far from it; an example being plantations of Scots Pine trees, often mistaken for natural formations, but actually planted by industry. Herein lies a complex reality we face as humans. Our existence predicts a certain amount of mark left upon our environment – the question is, to what scale and effect?

Travelling through the Central Belt of Scotland, McLaughlin has always wondered about these strange red hills rising seemingly out of nowhere. They are the Five Sisters (maybe a sardonic nod to the Three Sisters in Glen Coe), enormous shale bings, an outcome of the shale oil industry operating from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century. Today, covered as they are in grasses and scrub, they silently pass as potentially natural hills, a literal uncanny valley. Yet their obscurity veils a complicated history, one full of extraction, exploitation and social change.

McLaughlin’s paintings are a holistic response to the land’s fraught history. The works are made from predominantly two different earth pigments gathered at the site; one the characteristic rust-red of the shale, and the other a grey pulverised stone, found at the foot of the bing, part of a current flood prevention project. McLaughlin works with the deliberate process of grinding rock and making her own paints, which she then applies to remnant textiles, the seams visible, the edges often unfinished. The whole process is slow, considered and gentle. The contrast of these quietly powerful works made by hand in response to the mechanical mass extraction of something rapidly burned up for energy is stark. McLaughlin’s works are made from cast offs, waste material, and actual pollution. They are transformed. Much like the bings themselves, now designated as a Scheduled Monument, and an important site of recovering biodiversity, encouraging the growth of species that would not be there had the bings not been formed. Nature, like the works, is both at once fragile and resilient. By choosing to work in this way and in her use of materiality, McLaughlin ventures to do the difficult task of acknowledging and critiquing historic uses of the land, and at the same time offering new ways to think about our relationship to it – in other words, to offer hope.

Photo credit: Sam O’Donnell / A_Place